How Psilocybin Works

For most of us, the idea that a small piece of fungus could alter the way we think, feel, and perceive sounds almost unbelievable. Yet that is exactly what psilocybin, the active compound in psychedelic mushrooms and truffles, does. For centuries, it has been used in rituals and ceremonies as a tool for healing and insight. Today, modern science is beginning to catch up, showing us in detail how psilocybin works in the brain.

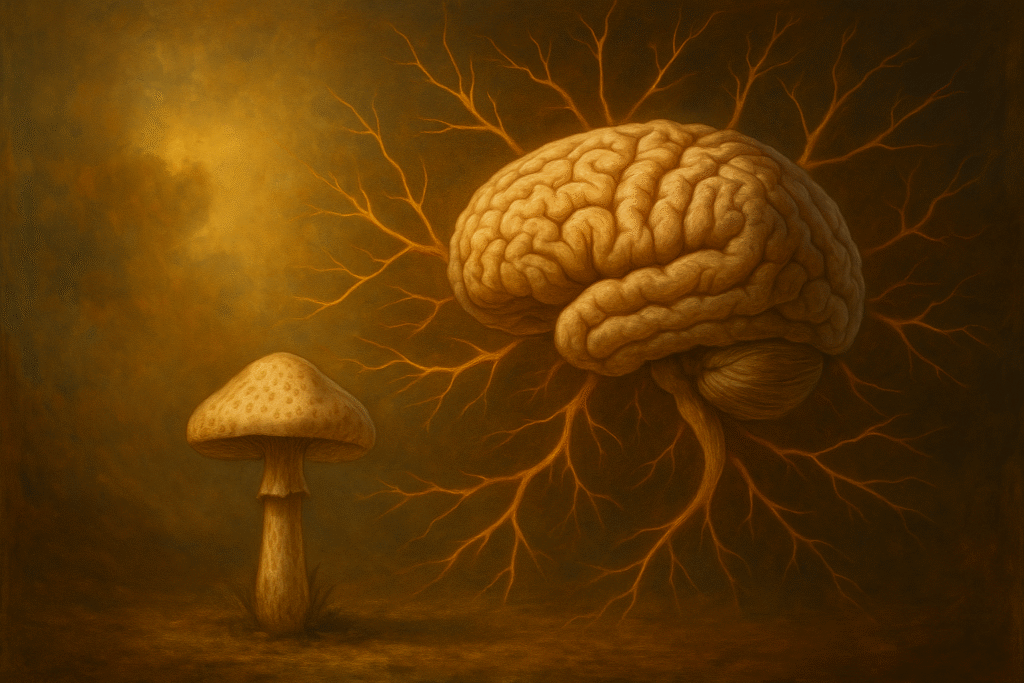

But here’s the truth: the magic lies not in wild hallucinations or kaleidoscopic visions. It lies in the subtle, intricate dance between psilocybin and the networks of the human brain. To understand microdosing, to understand psychedelics at all, we need to understand this dance.

So let’s explore what happens when psilocybin enters the body: how it’s transformed, how it binds, and why that binding opens doors to creativity, healing, and connection.

From Truffle to Molecule: Psilocybin Becomes Psilocin

When you consume a psilocybin truffle, you’re not immediately “activating” your brain. Psilocybin itself is a prodrug, an inactive precursor. Inside your body, enzymes rapidly convert psilocybin into psilocin, the molecule that does the real work.

Psilocin is a close chemical cousin of serotonin, the neurotransmitter that regulates mood, sleep, appetite, learning, and more. Because of this similarity, psilocin can “trick” the brain’s serotonin receptors into accepting it. Once bound, it alters the usual flow of signals, setting off a cascade of changes in perception, mood, and cognition.

This transformation from psilocybin to psilocin happens quickly, which is why effects can begin within 20–40 minutes of ingestion. In a microdose, the amount is small enough to avoid perceptual distortions, but still enough to gently shift the balance of brain chemistry.

From Truffle to Molecule: Psilocybin Becomes Psilocin

It all begins in the body. When you consume a psilocybin truffle, the active ingredient is not instantly “psychedelic.” Psilocybin is what scientists call a prodrug, inactive until your body transforms it. Once digested, enzymes quickly convert psilocybin into psilocin, the true active compound.

Psilocin’s structure is nearly identical to serotonin, one of the brain’s most important neurotransmitters. This similarity is the key. Because psilocin “looks” like serotonin, it can fit into the same receptors. It’s like a forged key that still opens the lock.

Within 20 to 40 minutes, psilocin begins circulating in the bloodstream, crosses the blood-brain barrier, and starts binding to serotonin receptors, particularly the 5-HT2A subtype. From there, perception, mood, and thought begin to shift.

Even in microdoses, this process is happening. The amount of psilocin is smaller, so the effects are subtler, but the mechanism is the same: a molecule slips into the serotonin system and begins to adjust the conversation inside your brain.

The Serotonin Connection

Serotonin is sometimes simplistically described as the “happiness chemical.” But it’s far more than that. It regulates mood, yes, but also learning, memory, sleep, digestion, even how we process sensory input. It’s woven into almost every dimension of our lives.

When psilocin binds to serotonin receptors, it doesn’t just mimic serotonin — it changes the way the system behaves. The 5-HT2A receptors, concentrated in the prefrontal cortex, are especially important. This region of the brain is responsible for complex thought, planning, and self-reflection. Stimulating these receptors disrupts the usual patterns of signaling, creating a cascade of effects.

Imagine a crowded town square where only a few voices dominate the conversation day after day. Psilocin enters like a new language, shaking the conversation loose. Suddenly, quieter voices are heard, and different people start talking to each other. The atmosphere shifts.

This is why psilocybin isn’t simply about “feeling good.” It’s about creating the conditions for new patterns of thought and perception to emerge, a temporary but powerful reorganization of the brain’s dialogue.

Quieting the Default Mode Network

One of the most groundbreaking discoveries in modern psychedelic science is psilocybin’s effect on the default mode network (DMN).

The DMN is active when we’re not focused on the outside world, when we’re daydreaming, worrying, or ruminating about ourselves. In many ways, it underpins our sense of ego. When the DMN is overactive, we get stuck: trapped in self-criticism, repetitive thought loops, or the heavy cycles of depression.

Under psilocybin, activity in the DMN decreases. At the same time, communication between brain regions that normally operate separately increases.

Think of your brain like a city. Normally, most traffic is funneled through a few main highways, creating traffic jams. Psilocybin temporarily closes those highways, and suddenly dozens of side streets open up. New neighborhoods connect. Ideas that never “met” before begin to flow together.

For some, this feels like a softening of the ego, less self-focus, more connection to others, or even to something bigger than oneself. For others, it feels like relief: the endless loop of anxious or depressive thoughts finally interrupted.

Even at microdoses, these effects can manifest subtly: a lighter inner dialogue, less harsh self-criticism, a small but meaningful shift in perspective.

Entropy and Flexibility: A More Open Brain

Robin Carhart-Harris, one of the leading psychedelic neuroscientists, describes psilocybin’s effect through the entropic brain theory. “Entropy” here doesn’t mean chaos, it means flexibility and openness.

In ordinary waking life, the brain is highly ordered. It relies on efficient, habitual patterns. This is useful: it helps us get through the day, make decisions quickly, and conserve energy. But too much order can become rigidity. Depression, addiction, and anxiety often lock the brain into repetitive loops.

Psilocybin increases entropy, loosens the rigidity. Brain imaging shows that under psilocybin, regions that normally don’t interact begin communicating. The brain becomes more like a jazz improvisation than a rigid symphony.

This flexibility is why people often describe insights, creativity, or breakthroughs. It’s also why psilocybin shows such promise in therapy: it gives the brain a chance to step outside of its old patterns and explore new ones.

Microdosing vs. Full Dose

The difference between a microdose and a full dose isn’t about mechanism, it’s about scale.

At high doses, psilocybin creates profound shifts: hallucinations, altered perception of time, dissolution of ego, and sometimes spiritual or mystical experiences. Brain scans show massive changes in connectivity, with networks cross-talking in ways they rarely do.

At microdoses, the same pathways are involved, but the changes are gentle. Instead of highways being shut down, perhaps a few traffic lights are adjusted. You don’t leave reality — you stay grounded, but with a touch more fluidity.

Many people describe it as “turning down the noise.” Focus sharpens. Moods lighten. Creativity feels closer to the surface. These effects may be subtle, but when repeated responsibly over weeks, they can accumulate into meaningful change.

Neuroplasticity: Building New Pathways

One of the most exciting areas of research is psilocybin’s role in neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to rewire itself.

Animal studies show psilocybin promotes the growth of new dendritic spines, the small branches that connect neurons. In some cases, these new connections persist weeks after the psilocybin is gone. This suggests psilocybin doesn’t just create temporary effects; it may actually help the brain form lasting new pathways.

For therapy, this is crucial. A single psilocybin session has been shown to create long-term improvements in depression and anxiety. For microdosing, repeated small exposures may gently encourage healthier patterns, making it easier to build positive habits, shift perspectives, or feel more resilient.

Neuroplasticity is the hidden bridge: the reason psilocybin’s effects can last far longer than the experience itself.

The Healing Potential

Psilocybin’s unique impact on serotonin systems, the DMN, and neuroplasticity has made it one of the most promising tools in mental health research today.

Depression: Clinical trials show psilocybin can produce rapid and lasting reductions in depressive symptoms, even in treatment-resistant cases.

Anxiety: Particularly in patients facing terminal illness, psilocybin has been shown to reduce fear and increase peace of mind.

Addiction: Studies suggest psilocybin helps people quit smoking, reduce alcohol use, or break free from compulsive behaviors.

Headaches and migraines: Anecdotal reports and pilot studies suggest psilocybin may relieve cluster headaches, one of the most painful conditions known.

What unites these outcomes is a common theme: psilocybin helps the brain escape rigid patterns and rediscover flexibility.

Why It Matters for Microdosing

Understanding how psilocybin works is the foundation for understanding microdosing.

Microdosing doesn’t unlock the full intensity of a psychedelic journey, but it engages the same systems: serotonin receptors, DMN activity, brain network flexibility, neuroplasticity. At small doses, these changes feel subtle, but they ripple into daily life.

A stressful day feels less overwhelming.

A creative idea comes more easily.

A relationship feels lighter, more patient.

This is why microdosing has captured so much attention. It’s not about escaping reality. It’s about tuning reality, gently and consistently, toward openness and possibility.

Final Thoughts

So how does psilocybin work? By becoming psilocin, binding to serotonin receptors, quieting the default mode network, loosening rigid patterns, and opening the brain to new connections.

At myco, we see this not as magic, but as a natural partnership between biology and experience. Psilocybin doesn’t force transformation, it creates the conditions where transformation is possible. Whether in the dramatic arc of a full dose or the subtle shifts of a microdose, it works by giving the brain room to move, adapt, and grow.

And that’s the essence of this practice: not escape, but expansion. Not fantasy, but flexibility. Not something foreign, but a reminder of what the brain is capable of when it’s free.